The Neuron That Started It All: McCulloch-Pitt Neuron

A Beginner's Guide to the McCulloch-Pitt Model

The Birth of an Idea

Think about the most complex machine you know, a car, a rocket, even the smartphone in your hand. What's fascinating is that each one is ultimately built from simple, fundamental parts: gears, circuits, levers. Artificial Intelligence, aiming to replicate the most complex machine we know – the human brain. Its most fundamental building block? The artificial neuron.

McCulloch-Pitts (MP) neuron proposed way back in 1943 by neurophysiologist Warren McCulloch and logician Walter Pitts, this wasn't just another idea. It was a revolutionary, simplified mathematical model designed to mimic the most basic functionalities of a biological neuron. Although the design was much simpler than the real thing, this small idea was an important step forward. McCulloch and Pitts showed that core concepts like receiving signals, making simple decisions (like "subscribe" or "don’t subscribe"), and transmitting results could be represented using logic and computation.

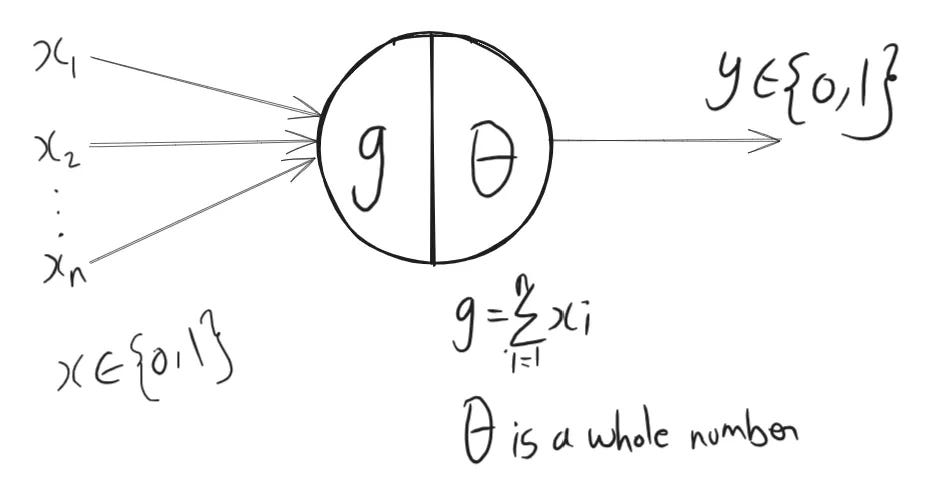

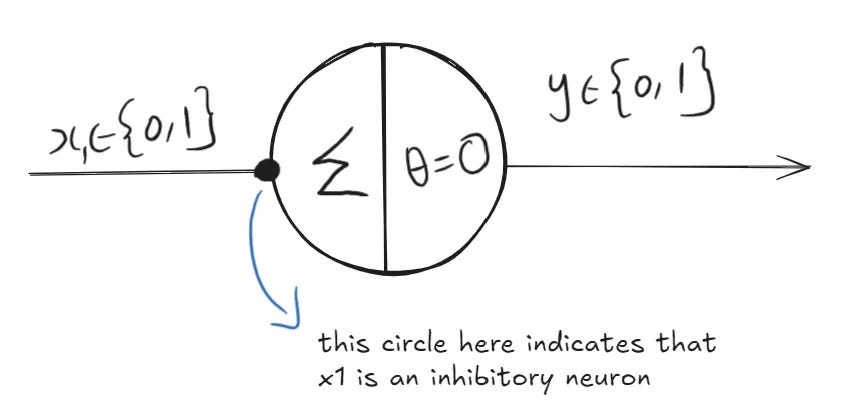

Below is a simple diagram of the MP neuron where, x’s are the input and y is the output. Summation of x’s is denoted by g and θ defines the threshold value. If g is > θ the output y is 1, else its 0. We will discuss this in detail with an example in the following sections.

This move lit the fuse for the entire field of artificial neural networks (ANNs) and modern AI, demonstrating that creating thinking machines based on neural principles wasn't just a pipe dream but rather a worthwhile endeavor. Let's break down how this pioneering model actually worked.

How It Works: The MP Neuron Explained

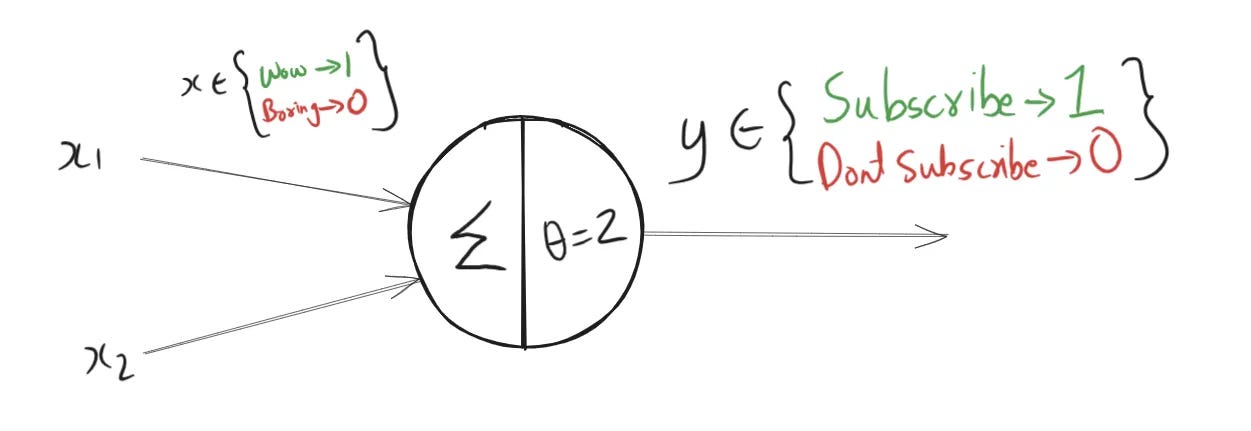

Imagine a McCulloch-Pitts neuron tracking your reaction as you read this article. Right at the start, you either go "wow, this looks promising!" or "ugh, not impressed." At the end, again, you either feel "wow, that was worth it" or "this was boring."

Each of these reactions is converted into a binary input for the neuron:

A "wow" is a positive signal →

1A "bad" or negative feeling is a neutral/ignored signal →

0

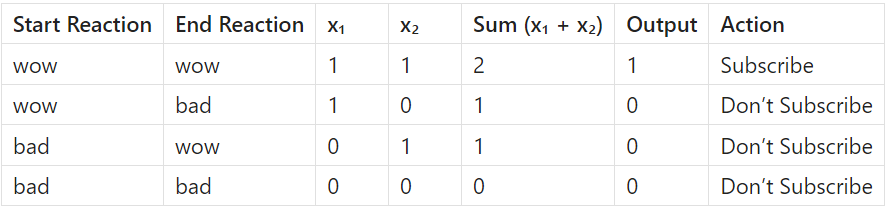

The neuron adds up these two inputs. If both the start and end reactions are "wow", the sum is 2, which meets the threshold, so the neuron fires and prompts you to subscribe to the DailyDataDigest.

If either reaction is "bad", it contributes 0, lowering the sum. If the total is less than 2, the neuron doesn’t fire, meaning you’re not prompted to subscribe.

Key Ingredients of the McCulloch-Pitts Neuron:

Inputs (x₁, x₂): Binary signals based on your reaction at the start and end.

1if reaction = "wow"0if reaction = "bad"

Aggregator (∑): Adds the input signals.

Threshold (θ): Set to

2Decision Rule (Activation Function):

If

x₁ + x₂ ≥ 2, the neuron fires (Output = 1) → SubscribeIf

x₁ + x₂ < 2, the neuron does not fire (Output = 0) → Don’t Subscribe

Output Table

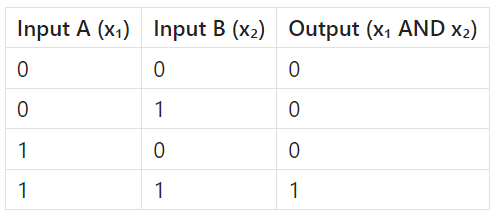

What we’ve described is a classic AND gate in action, implemented through a McCulloch-Pitts neuron.

The neuron receives two binary inputs: one for your reaction at the start, and one at the end.

Both inputs must be 1 (i.e., both moments must feel like “wow”) for the neuron to fire.

If even one input is 0 (i.e., if you feel “bad” at either the start or the end), the neuron does not fire.

This logic exactly mirrors the truth table of a standard AND gate, where:

So in this case, the McCulloch-Pitts neuron behaves just like an AND gate — it outputs 1 (fires) only when both inputs are 1. The threshold of 2 ensures this condition is met only when both "wow" moments occur.

Thus, your subscription decision here isn't emotional. It's cold, logical, and classically digital. Just like an AND gate.

But wait! What if we want to simulate a NOT gate next? It’s a little trickier with MP neurons but totally doable using inhibitory inputs.

Inhibitory Input

The original McCulloch-Pitts model can only add positive (excitatory) inputs, which limits it to simple logic like AND and OR. While excitatory inputs (value 1) push the neuron toward firing, even a single inhibitory input (value 1) forces the neuron to stay silent—outputting 0 regardless of other inputs. This models biological neurons where certain signals actively block activation.

How It Works:

The neuron has:

One inhibitory input

x1One bias input always set to

1(excitatory)

The neuron fires (outputs 1) only if:

The inhibitory input is

0The bias input is active (

1)

If the inhibitory input is

1, it blocks the neuron, and the output is0.

Input (x) Output (NOT x) 0 1 1 0

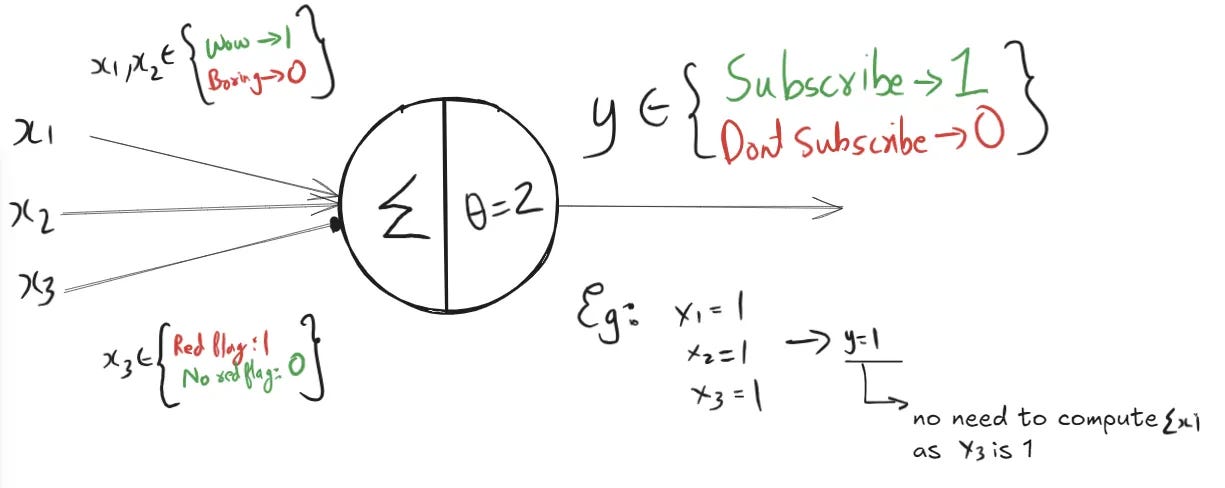

Continuing with our previous example

A promising start to the article generates an excitatory input,

x₁ = 1.A satisfying conclusion provides a second excitatory input,

x₂ = 1.However, spotting a "red flag" in the middle, such as misinformation or an exaggerated claim, triggers a crucial inhibitory input,

x₃ = 1.

The neuron's decision rule is based on a threshold of 2. The sum of the excitatory inputs, x₁ + x₂, equals 2. In an ordinary scenario, this sum would meet the threshold and cause the neuron to fire, representing a positive action like subscribing.

However, the inhibitory input x₃ fundamentally changes the outcome. When the inhibitory signal is active (x₃ = 1), it acts as a veto, overriding all other signals. Despite the excitatory sum meeting the threshold, the inhibitory input forces the final output to be 0. As a result, the system does not prompt you to subscribe.

The Limitations: Why We Needed More

No shades of gray: All inputs and outputs must be all binary (0 or 1). Thus, the system is inappropriate for tasks where the variables are continuous, like to analyze image pixel brightness, audio signals, or stock prices. It simply cannot express how strong or weak a given signal was — rather, it states if the signal was present or absent.

The biggest drawback: No learning! The threshold value (θ) has to be set arbitrarily. It cannot learn from data, adjust weights, or somehow enhance its performance over time, and this is a glaring deficit given that the whole modern field of machine learning and neural networks rests on learning from experience.

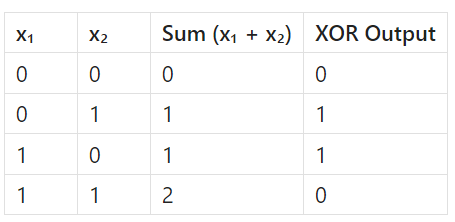

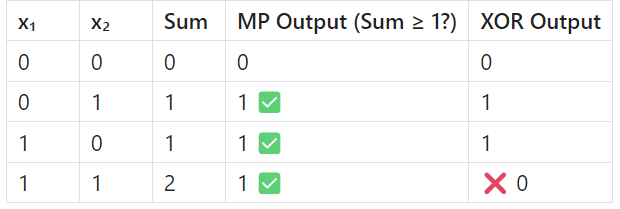

Limited problem-solving: McCulloch-Pitts neurons can solve only linearly separable problems, i.e., problems that can be separated using a straight line (or plane). Some, however, cannot be solved this way: the classic XOR problem, for instance. In XOR, the neuron fires only when exactly one input is 1; it must not fire when both are 1. A linear model is incapable of capturing this relationship: it needs non-linear decision boundaries and hence multiple layers or some other kind of neurons.

Lets take the value of θ = 1

even if θ = 2 the MP neuron will fail. No matter what threshold (θ) you choose, the MP neuron can't match all XOR outputs correctly. That’s because XOR is not linearly separable — you can’t separate the 1s and 0s with a single line in the input space.

Conclusion: From a Simple Spark to a Raging Fire

In a nutshell the McCulloch-Pitts neuron serves as a basic binary threshold unit and is a fundamental model in artificial intelligence. Its fundamental ideas—inputs, a summation, a threshold, and an activation rule remain at the core of the sophisticated neurons found in deep learning networks today.

The MP neuron is ultimately best understood as the fundamental "ancestor" of contemporary artificial intelligence. Even though it was straightforward on its own, it was the crucial spark that ignited the entire neural network field and produced the highly complex and powerful systems we see today.

Resources:

Here are some resources that has helped us and may help you out too!

Get started with Deep Learning: Roadmap to learning Deep Learning

A quick guide to Deep Learning: The Little Book Of Deep Learning